In Which the Sindar Put Down Roots, Dwarves Emerge and Get Right To Work, and Melian Puts Up An Orc-Proof Fence

As we should know from The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien likes to tell stories in a sort of zigzag chronology. We can set aside for a moment Fëanor and his rage-quit of Valinor. This tenth chapter, “Of the Sindar,” rewinds the timeline back to when Olwë and his Teleri first “sailed” off to Valinor on Ulmo’s island-boat, filling us in on what’s been happening in Middle-earth ever since. It’s much darker here, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. We see what the Teleri have been up to, discover which hardy and hirsute people are now on the scene, then witness the first battle against Morgoth and his Orcs! This is, in part, stage-setting for the Noldor’s return, but one takeway from this chapter might be: Everything’s not about you, Fëanor, and your people aren’t the only ones we have to care about.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Thingol – Sindarin king, sitting pretty

- Melian – Maia queen, fencemaker

- Círdan – Sinda, lord of the Falathrim, shipwright mofo

- Denethor (no, not that Denethor) – Green-elf king

Of the Sindar

This chapter can be divided into four sections. The first three mark each of the unspecified ages during which Morgoth—excuse me, Melkor at this time—is doing hard time in Mandos State Penitentiary, and the fourth is what happens after his release. It’s been surmised outside of this book that each age is close to a thousand years as we measure them, but the word “age” could just as well be replaced with “a long-ass time.” The point being that Melkor’s tanned hide isn’t around to bother anyone for a good long while.

Which doesn’t mean that he hasn’t left a bunch of his minions around to make trouble. Indeed, Middle-earth’s got plenty of those, and they’ll show up in Beleriand in greater numbers in this chapter. So let’s start with the first age of Melkor’s chaining. It’s worth noting that these ages are not to be confused with the proper noun Ages to come (First Age, Second Age, etc.).

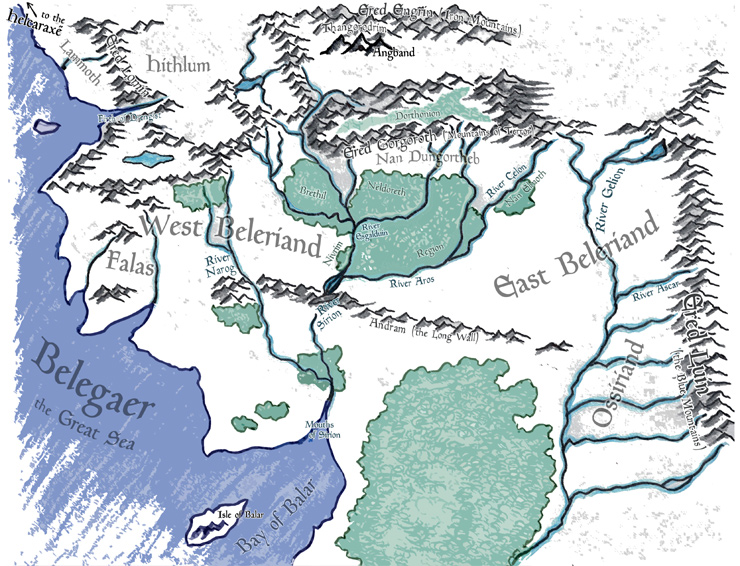

Melkor’s Captivity—Age One

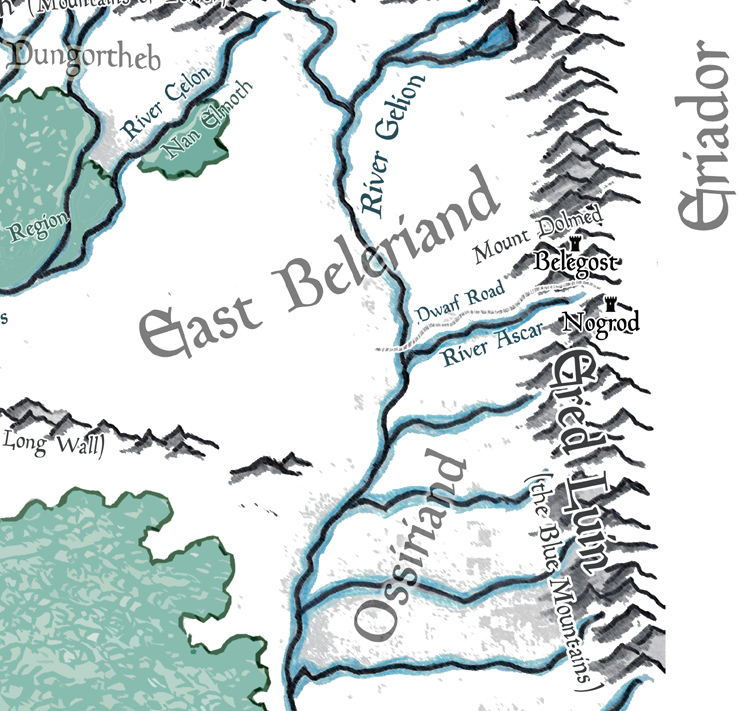

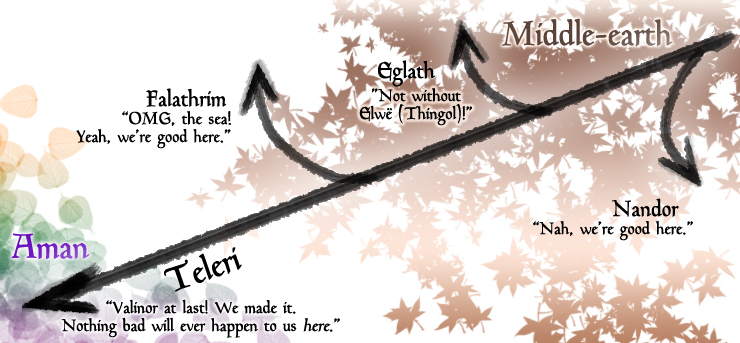

If you remember from earlier chapters, once Melkor was locked up, Oromë and Ulmo led three hosts of the Eldar westward and over to Valinor. But that journey left behind a whole bunch of loitering Elves from that third host: the Teleri, the Last-comers, (the Johnny-Come-Latelies, but never to their faces.) They’d become scattered across both Beleriand and Eriador (two side-by-side regions of Middle-earth divided by the Ered Luin, the Blue Mountains).

Now, all of these folks are considered Moriquendi, Elves of the Darkness, because they bailed on going to Valinor in its Tree-lit heyday. And remember, there is still no such thing as a sun and/or moon in Arda. Middle-earth is in perpetual darkness, lit only by starlight and whatever lamps or torches the Elves make for themselves. But, because Melian the Maia had come over at the beginning of this period, “there was life and joy, and the bright stars shone as silver fires.” The Elves’ night vision seems pretty sharp, so it’s not like the dim ambience actually stalls their explorations, migrations, or settlements. All in all, it’s like constant twilight. And they love it.

In any case, now that all those highfalutin Calaquendi (Elves of the Light) are out of Middle-earth’s hair, let’s talk about these left-behinders. Or, at least those on this side of the Blue Mountains, all of whom at least initially tried to get to Valinor but gave up for various reasons. These are all the Sindar, “the Grey-elves of starlit Beleriand,” and all of them are loosely ruled, near and far, by Thingol, King Greymantle (the Elf formerly known as Elwë) and Queen Melian.

The Sindar are made up of the two basic groups of ex-Teleri.

- The Falathrim, those who decided only at the last minute not to go to Valinor; now a bunch of mariners, they hang out by the coast and are led by Círdan the Shipwright.

- The Eglath, those who didn’t even get as far as the sea because they wouldn’t stop searching for their leader when he went AWOL; but now he’s back so all is well.

So Thingol’s kingship encompasses all of these Eldar in Beleriand, though they’re fairly scattered. Some are grouped around Círdan at the coast, while others are gathered around Thingol himself. Still more are just far-flung in woods and hills, as far as all the way up to the Blue Mountains. Sure, there are some monsters in the wild, bred during the reign of Utumno, Melkor’s old factory of evil, but it’s not in business anymore. These beasties aren’t organized and aren’t really a big threat. And Sauron might be holding a torch for his master somewhere, but he’s not yet sliding into his place as Dark Lord. That’s way off.

So, right at the end of this first age of Melkor’s incarceration, in a forest known as Neldoreth, Thingol and Melian have their first and only child: Lúthien. Now we’ve heard tell of her thanks to The Lord of the Rings, right? She’s the Elf-maid that Aragorn first thinks he’s looking at when he meets Arwen, and the one whose legend he tells the hobbits about at Weathertop. We’re told even then that “she was the fairest maiden that has ever been among all the children of this world.” And we may also remember that “from her lineage of the Elf-lords of old descended among Men.”

All right, so Lúthien is going to be important—much later, of course—at bringing together Men and Elves. But still, that’s far off. Remember, almost no one’s even heard of Men yet. At least, not in Middle-earth. It’s kind of odd: Sometimes Tolkien drops a name early on just so you’ve got it when it comes around again much later. And sometimes he gives absolutely no warning when he introduces a character who would have been around the whole time (*cough* Huan). But with this sort of literary inconsistency, we must be fair to the professor and remember that The Silmarillion was organized and published after his death. He might have tied it up more neatly on his own.

And hey, it might be worth noting that this is the first time we observe a Maia having offspring. The Valar themselves do not have children together, and Maiar who are married to one another (like Ossë and Uinen) do not. But here Melian’s union is with one of the Children of Ilúvatar—so together they can reproduce. Yet Lúthien will be an only child. Sure, we were told that Ungoliant—who again may or may not be Maiar herself, but who is certainly some variety of immortal spirit-being—does eventually mate with spider monsters that Melkor had bred. But, well, the less said about that the better. The point being that those spider-fellows, before being inevitably devoured by their ill-considered girlfriend, were mortal. And that’s why Shelob and her elder siblings would eventually come to be.

Melkor’s Captivity—Age Two

It came to pass during the second age of the captivity of Melkor that Dwarves came over the Blue Mountains of Ered Luin into Belerian. Themselves they named…

Whoa whoa! What? Dwarves just “came over”? What about the Dwarves woke up?!

No fair! Don’t they get their own Cuiviénen? Alas, we don’t get any information about how this all went down. And why? Because this is The Silmarillion, not The Arkenstiliad; this book is told, more or less, from the point of view of the Elves. And more specifically, it’s obviously centered around the Noldor—although they’re certainly the most willful group of Elves in these ancient times. This book would be a bit different if told from the Vinyarin or Telerin point of view. Especially after the Kinslaying.

Point being, if we had Arda’s history from the POV of the Dwarves, it would probably be quite another thing entirely. First off, Aulë would be center stage and there’d be a whole lot less bother about glow-in-the-dark trees. Still, I can’t help but wonder: did the Dwarves wake up on the shores of some subterranean lake? That would be cool. Were they bearded from the get-go, or were they born as children with five-o’clock shadows and then had to grow them out? I do wonder if Aulë was given a heads-up when the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves—which he’d made with his own hands long before—first stirred. But I’m guessing not. Ilúvatar alone chooses the time and place of each race’s awakening. Even Manwë the King of Arda is on a need-to-know basis with these things.

The Silmarillion can be frustrating with its omissions, for which the History of Middle-earth series (for all its labyrinthine strands of lore) can prove an antidote. Not to mention the collected Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. In fact, in the draft of such correspondence, he wrote, speaking of Ilúvatar:

And he commanded Aulë to lay the fathers of the Dwarves severally in deep places, each with his mate, save Dúrin the eldest who had none.

So at least in Tolkien’s mind there were also Six Mothers (even if they weren’t called that) right from the start. And interestingly, the Dwarves didn’t all awaken in the same place! Seems like they had to find each other. Can you imagine if Elves had popped up in different places, too? Can you imagine how many groups and subgroups Tolkien would have invented for them, and how much tarrying it would take for them to all meet up and make group decisions? Oromë and the other Valar would have really had their work cut out for them!

But Dwarves, not being part of Ilúvatar’s original schematics for Arda—more of an impromptu side project—are kind of an exception. So he handled their arrival differently.

In any case, it’s not until Dwarves come marching through the mountains at the east end of Beleriand that the Sindar are even aware of them. And these aren’t proto-Dwarves or anything. They’ve already been around long enough at this point to have developed their own rich culture. They’re already smiths and masons and industrious workers—hell, they’ve already built some cities back in Eriador beyond the Blue Mountains—one of which is Khazad-dûm (of “The Bridge of Khazad-dûm” fame!), “greatest of all the mansions of the Dwarves.” But the Sindar haven’t seen these other cities; they just hear the Dwarves speak well of them.

Still, the Elves are gobsmacked. I mean, other people who are not Elves have shown up! And they talk, too?! The Elves had originally named themselves the Quendi, “those who speak with voices,” but now that name’s a bit outdated. Notice, though, that they don’t immediately wonder if maybe the Dwarves are the Secondborn of the Children of Ilúvatar…because the Sindar know nothing about Men. The Valar have kept that to themselves. Remember, Melkor was the one who let that Man-shaped cat out of the bag back in Valinor, and then only to some of the Noldor just to get all that rebel talk going. But here on Middle-earth, there’s been zero chitchat about other races.

And if Melian knows about Men—let’s face it, she probably does, she was there at the Music of the Ainur—she isn’t telling. Perhaps she doesn’t think it’s her place to speak of these things. Not even to her husband, the king of the Sindar. He’s on a need-to-know basis, too. Which is just as well—he won’t have a great track record concerning Men for a good long time, even when they do show up. Again, there are still no Men on the scene, so it’s a moot point.

But back to the Dwarves.

In the darkness of Arda already the Dwarves had wrought great works, for even from the first days of their Fathers they had marvellous skill with metals and with stone; but in that ancient time iron and copper they loved to work, rather than silver or gold.

We’re told that the Sindar, upon meeting the Dwarves, come up with two names for them. One, the polite one, highlights their expertise: Gonnhirrim, the Masters of Stone. That’s cool. Then there’s the less-than-polite one: Naugrim, the Stunted People. Damn it, Elves! Think if it if you must, but do you have to say it? And then hand it down through the ages to be recorded for posterity in The Silmarillion as the primary name the Elves use? Although to be fair, remember that Elves have given other Elves some backhanded names (Teleri, “the Last-comers”), too. You’d at least think they’d come up with something a little more neutral-sounding. Like the Bearded Folk, the Scowling People, or the Strong-handed Chaps. Nope, they went with the Stunted People.

But you know what? The thick-skinned Dwarves bear it with all the stoicism and durability that Aulë put into them. They take the high road in dealing with the Elves. Curiously, for all their love of words, the Elves find the Dwarven language of Khuzdul “cumbrous and unlovely” and struggle to learn it. If you recall from the chapter “On Aulë and Yavanna,” the Dwarves’ language was even devised for them by Aulë himself. It’s a Vala-made tongue!

Whereas the Elves were not given a language: they got to make their own, which suits them. Their languages are a big part of their identities (just as the creation of these languages was obviously a big part of Tolkien’s own). And so from that original Elven language spoken on the great westward march, all these thousands of years later we’ve primarily got two descendant tongues at hand: Quenya, which the Noldor and the Vanyar are speaking way over in Valinor, and Sindarin—what everyone here in Beleriand speaks.

Few Elves ever become fluent in Khuzdul, though I like to think that those who interact with the Dwarves try to learn some basic conversational expressions. A typical Sindarin-to-Khuzdul phrasebook would probably include helpful questions, comments, and salutations like:

- “Well met.”

- “A star shines on the hour of our meeting.”

- “I’m sorry, can you repeat that? I didn’t understand.”

- “Excuse me, can you direct me to the nearest river?”

- “Could you recommend somewhere I might tarry?”

- “I will not buy this record, it is scratched.”

But more importantly, the Dwarves are okay with this. They’re secretive about their Aulë-made tongue, and are more than willing to learn the Sindarin language to do business with the Elves. Being both productive and practical, the Dwarves build a trade road through the mountains so that they can come and go more easily between Thingol’s wide realm and their own two closest cities: Belegost and Nogrod.

Ever cool was the friendship between the the Naugrim and the Eldar, though much profit they had one of the other; but at that time those griefs that lay between them had not yet come to pass, and King Thingol welcomed them.

Ilúvatar himself warned about such griefs back when he told Aulë that “often strife will arise between thine and mine, the children of my adoption and the children of my choice.”

In typical Tolkien fashion, he looks forward beyond this chapter to point out that when the Noldor do finally return to Middle-earth, they’ll actually get along with the Dwarves better still, due to their shared interests in gems, metal, and the industrial arts. In smithing, especially! And of course, both the Noldor and the Naugrim are fond of Aulë and the skills they’d learned from him separately. But that’s the future. Right now it’s just the Sindar and the Dwarves, and they struggle to find common ground. The Dwarves don’t seem all that interested in trees (except for wood!), leaves, and singing water. And forget about the sea!

Except…

Melkor’s Captivity—Age Three

Because she’s awesome and because she “had much foresight,” Melian suggests to Thingol that they consider the defense of their sprawling kingdom. This lovely peace they’ve been enjoying for thousands of years isn’t going to last. She knows that while Melkor has been locked up, he’ll be tried again soon enough. Let’s think about that. Melian has spent plenty of time in the company of the Valar, first in the Timeless Halls beyond Eä, then on the island of Almaren in the days of the Lamps, then in Valinor before drifting over to Middle-earth in search of a husband. So she’s well-informed and probably has a good idea which direction Manwë will go when the moment of judgement is at hand. Maybe Melkor will do right by his kin! Or maybe not. And if not, then the Elves need to be prepared for trouble.

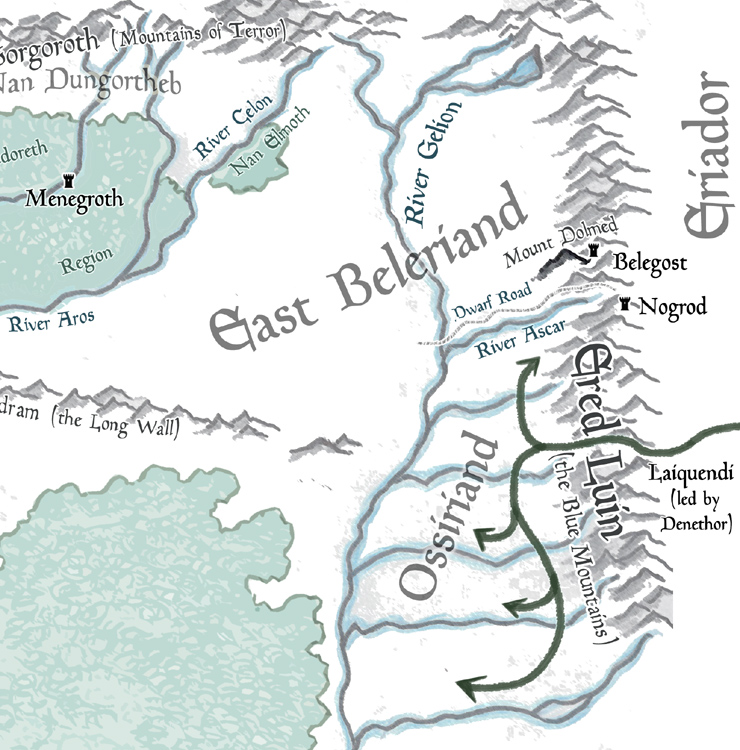

So Thingol decides it’s time to put down some stone roots. He reaches out to his associates in the Dwarf city of Belegost and commissions them to help make a defensible fortress right there between the forests of Neldoreth and Region (REH-gee-ohn, with a hard g) on the River Esgalduin, south of the Mountains of Terror and the forested highlands of Dorthonion. Right away the Dwarves get busy. They’re happy to do it, as they “were unwearied in those days and eager for new works.” In exchange Thingol gives them (or, let’s face it, re-gifts) many pearls which Círdan had sent over to him from the coast.

During this time, Melian herself “taught them much that they were eager to learn”—which is a seriously intriguing and vague statement! What does a wise and powerful Maia, whose motif is songbirds and whose favorite thing to do back in the day was enjoy long walks in the gardens of Lórien, have to teach gruff, down-to-earth, iron-minded Dwarves?! Possibly what it’s like to hang out with Aulë? They’re huge fans of their maker. They have burning questions like: What are his hopes and dreams, his desires and aspirations? Does he smith all the time or does he set aside a certain portion of the day? How tall is he? Where does he sleep? Does he sleep? What does he eat for breakfast? Does he put jam on his toast or doesn’t he put jam on his toast? If not, why not, and since when?

Thus comes into being Menegroth, the Thousand Caves. It starts off with Dwarves doing all the work and shaping this Elf city like a Dwarf city—meaning, in part, that they build underground, crafting something like a sprawling, elegant dungeon with carven chambers and tunnels instead of sky-reaching Elvish towers. But eventually the Sindar get inspired to join in, and therefore the place becomes a wondrous combination of Elf and Dwarf hands. Even Melian contributes with visions of Valinor which are then carved into the stone. Throughout Tolkien’s legendarium, whenever people work on something in concert of their own free will, things become greater.

The pillars of Menegroth were hewn in the likeness of the beeches of Oromë, stock, bough, and leaf, and they were lit with lanterns of gold. The nightingales sang there as in the gardens of Lórien; and there were fountains of silver, and basins of marble, and floors of many-coloured stones. Carven figures of beasts and birds there ran upon the walls, or climbed upon the pillars, or peered among the branches entwined with many flowers. And as the years passed Melian and her maidens filled the halls with woven hangings wherein could be read the deeds of the Valar, and many things that had befallen in Arda since its beginning, and shadows of things that were yet to be. That was the fairest dwelling of any king that has ever been east of the Sea.

“…and shadows of things that were yet to be.” Just goes to show you how even Melian has a bit of prescience about her. Had she spent some time in the company of Mandos, too, before coming over to Middle-earth? She’s so cool.

But anyway, picture the Wood-elf king’s halls from The Hobbit, the storied elegance of Rivendell, and the gardens of Lothlórien in Fellowship and know that this wondrous city is their spiritual and architectural ancestor—a place the likes of which will not be matched even by the Noldor when they come! That’s really saying something.

Untold years of peace and harmony go by and then one day a new wave of “fell beasts” begin to appear in Beleriand, coming from the east where before they’d only troubled the Sindar’s old cousins who never made it this far. And what sort of beasties are we talking about? Tolkien doesn’t give us much detail, but calls them “creatures that walked in wolf-shapes” (so probably werewolves!) and “other fell beings of shadow.”

But also Orcs! But not in great number, not yet. This is still the third age of Melkor’s imprisonment, and the Orcs that have been made are only testing the waters, as it were, and while they are making their first appearance among Elves, they are not so aggressive yet. The Sindar don’t even know what to make of them. They’re ugly, but they’re kind of people-ish, aren’t they? They think the Orcs might be some sort of degenerate Elves of the Avari kind that must have turned “evil and savage in the wild,” having never departed Cuiviénen for Valinor like everyone else. And I guess that’s not far off the mark.

In any case, this influx of monsters in Beleriand is enough to stir Thingol to action. He calls for the making of weapons. And it’s the Dwarves who comply, because it’s totally their thing. They already know how to make weapons. Soon enough Melkor will be nudging the Noldor into forging weapons over in Valinor, but here in Beleriand it’s wall-to-wall Dwarves taking up the challenge because they’re “a warlike race of old.” See, they’ve already fought against monsters and even their own kind. We don’t get a lot of detail about this, but it’s fairly obvious that Dwarves can be cranky. Their cities and lordships feud with one another.

We’re told that the craftsmen of the city of Nogrod are the best of the best and one day a particular Dwarf, Telchar, will come from this same group of blacksmiths. Telchar will forge at least three notable items in days to come—one of which will be a little sword you’ve probably never heard of known as Narsil. But for now, the Naugrim, the Stunted People, make Thingol’s weapons for him, and the Sindar also pick up a few skills in smithcraft in the process.

Yet in the tempering of steel alone of all crafts the Dwarves were never outmatched, even by the Noldor, and in the making of mail of linked rings, which was first contrived by the smiths of Belegost, their work had no rival.

So steelworks will always be Dwarves’ best work, and their proficiency beats out even the high and mighty Calaquendi Noldor. Not bad, Dwarves! And with the armories of Menegroth now stocked with swords, axes, spears, helms, and “long coats of bright mail,” the evil creatures now stalking Belerian are kept at bay. They got this.

So hey, remember back when the Teleri were doing all their splitting up a few chapters back? Let’s recap:

Well, long ago now, the splinter group known as the Nandor, “those who turn back,” had stayed east of the Misty Mountains. And they’ve since wandered around and fragmented themselves who knows how many times! Being a peaceful and woodland-dwelling bunch who are not well armed, they’ve been harrassed by this recent surge of fell beasts. By this time, however, the son of the Elf who first turned them back takes charge. His name is Denethor, a name very well known to Rings readers. And this eponym isn’t the only Elvish name swiped by the line of the Stewards of Gondor, either. (We’ll see it again later.)

In any case, Elf-Denethor is the Nandorin lord who hears at last of the power and successes of Thingol over in Beleriand. So he gathers up as many of his people as he can—rounding up and herding Elves is truly more art than science in this world—and together they cross the Misty Mountains, at last. Then they trek across the wide region of Eriador, then over the Blue Mountains. Thingol welcomes them “as kin long lost that return,” and Denethor settles his people on the eastern frontiers of the kingdom. And why do they just cross the mountains and then stop right there? My guess is because it’s Ossiriand, the Land of Seven Rivers. You can never have enough waterfront property if you’re an Elf of Teleri stock. So this ex-Teleri, ex-Nandor group of Elves are now called the Laiquendi, or Green-elves, because to them, green is the new (and forever) black.

And things are great for Beleriand for a good long while. The Sindar and their Naugrim business partners prosper. In the royal court, Melian’s beauty is likened to the noon, and daughter Lúthien’s is likened to the dawn in spring. (Which is an especially interesting choice of words, considering dawn must mean a very different thing during a time when there is yet no rising sun.)

King Thingol upon his throne was as the lords of the Maiar, whose joy is as an air that they breathe in all their days, whose thoughts flow in a tide untroubled from the heights to the deeps.

Truth is, it’s impressive that Thingol is likened to a lord of the Maia, but his wife is an actual Maia. Despite Melian’s lauded beauty in her form as one of the Elder Children of Ilúvatar (i.e. Elf-like in body), I submit that he’s the trophy spouse. He’s obviously a great leader, but so much of his power comes from her; it’s Melian’s wisdom and foresight that glues everything together in their kingdom, and things will be fine as long as Thingol keeps taking her advice. But hey, she obviously loves the guy, and the Sindar in turn love their king. That said, there’s no way he doesn’t have at least one Jareth-style outfit.

Oh, and get this: we’re told that Oromë himself comes riding through Beleriand, still. The Valar will become decidedly scarce once armies start shuffling around Middle-earth. But for now, the Elves who hear or spy Oromë on the hunt are always afraid at first—perhaps due to Melkor’s very old “dark rider” propaganda—but when they hear his hunting horn echoing through the hills, they take heart. The fell beasts that have been creeping in really split when old Oromë shows up! If only he would come around once the Melkor-smelling shit hits the fan.

And it will. In due time, and unbeknownst to everyone in Middle-earth, Melkor’s captivity comes to an end.

Melkor Unchained

And, for a while, things are fine. But slowly and surely, as we already know, Melkor undermined the Valar’s influence on the Noldor, stirred up trouble, and then finally earned his new name. So things way over in Valinor get dark, and neither the Sindar nor Melian know anything about it—this will be an important point to understand later. Yet the spiritual gloom that reigns with the Darkening of Valinor is felt, if not seen, even here in Beleriand. Whatever little bit of news used to go back and forth between Valinor and Melian—who is the only Maia on Middle-earth that we know about—ceases.

And then one day a horrid cry rings across Beleriand and echoes in its hills and valleys. Everyone hears it, everyone shrinks from it in a moment of fear, and they don’t know whose deathly voice it is. But a voice loud enough to be heard across hundreds of miles is surely loud enough to be heard by those Balrogs lurking in that old ruin to the north….

That’s right, we’ve been here in this moment before. Ungoliant and Morgoth are here in Middle-earth now, in the flesh. And that great shout was Morgoth changing his relationship status with Ungoliant. They’ve gone from “it’s complicated” to totally blocking each other. I mean, it’s obvious. At no point in the future does Morgoth even try to reconnect with her, or seek her out for one more heist for old times’ sake or anything like that. They’re both just pretending the other doesn’t exist anymore.

Anyway, after their little scuffle and the arrival of the Balrog Brigade, Ungoliant comes scuttling east and south, down towards the forests of Thingol’s realm! Uh-oh. No way will the Elves be able to handle her! She could gobble up these Moriquendi like nothing!

But nah-ah, girlfriend…

…by the power of Melian she was stayed, and entered not into Neldoreth, but abode long time under the shadow of the precipices in which Dorthonion fell southward.

In my head, I like to imagine Melian and Ungoliant making eye contact even from a distance, right there at the edge of the forest. It’s such a shame that we don’t get more detail around scenes like this. This is the Sindar’s queen defending them all, unleashing her Maiar power like a giant can of RAID MAX® Spider Killer. Of course it wouldn’t kill Ungoliant—a bunch of Balrogs had already tried—but it’s enough to send her scurrying away.

And listen, I know the female characters in Tolkien’s legendarium aren’t numerous, but each and every one of them is goddamned interesting. I can’t always remember the sixth son of Fëanor off the top of my head, nor recall half the Men in the House of Bëor, but I will always remember Éowyn, Galadriel, Melian, Lúthien, Ungoliant, Haleth, et al.

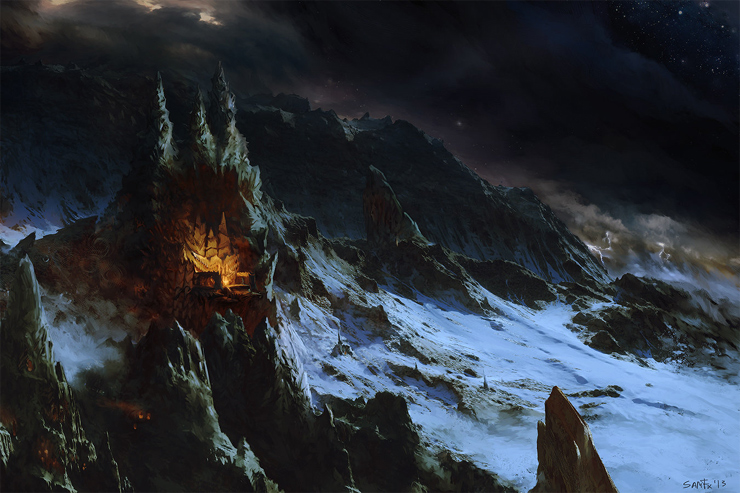

Ungoliant is forced to settle beneath Ered Gorgoroth, the Mountains of Terror, where she makes a real mess of them with her nasty-ass webs, clinging darkness, and (eventually) her hideous offspring. With his former ally unable to hold him to his promises, Morgoth is free now to renovate and rebuild Angband. Its dungeons grow deeper and more advanced, while the “reeking” mountains of Thangorodrim are raised up above them. Now he’s sitting on his throne with the three Silmarils mounted on his head in an iron crown. Right, we touched on all that in the last chapter. So, what’s next for old Morgoth? It’s not like the Black Foe of the World is going to just sit and mind his own beeswax.

Say, why not reopen Project Orc? Morgoth had been interrupted not long after making Orcs in the first place, the act that was “the most hateful to Ilúvatar.” Yes, he’d twisted and bred them thousands of years earlier, and because they were made from Elven stock, they could biologically reproduce like any of the Children of Ilúvatar—an act best not deeply considered (but yes, this means there would be males and females alike). But left on their own all this time, they had not become plentiful as natural creatures might. Why would they? Nothing’s natural about them. They were probably killing each other off as fast as they could reproduce, and I’m doubtful they reproduced much. They’re like the pandas of the monster world. Kind of. But only in that one, very specific way.

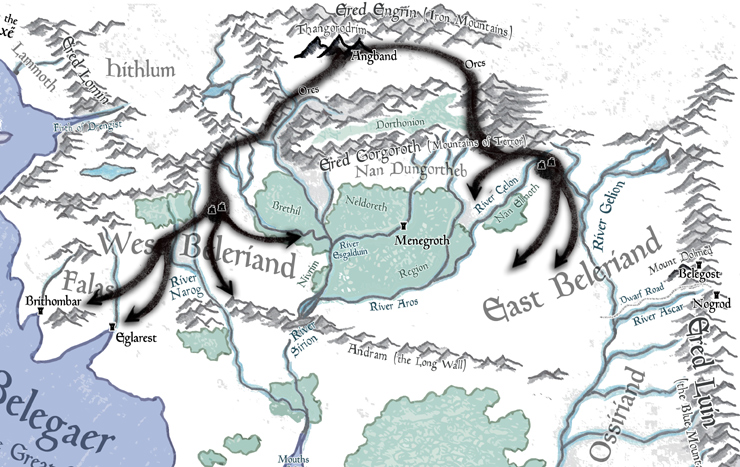

But now Morgoth has returned to oversee things! He applies his talents for corruption, squandering some more of his Valar-level power in the process, and makes the Orcs into the threat he’s dreamed of. And once their numbers are great, he sets them loose to plunder and destroy.

Now the Orcs that multiplied in the darkness of the earth grew strong and fell, and their dark lord filled them with a lust of ruin and death; and they issued from Angband’s gates under the clouds that Morgoth sent forth, and passed silently into the highlands of the north.

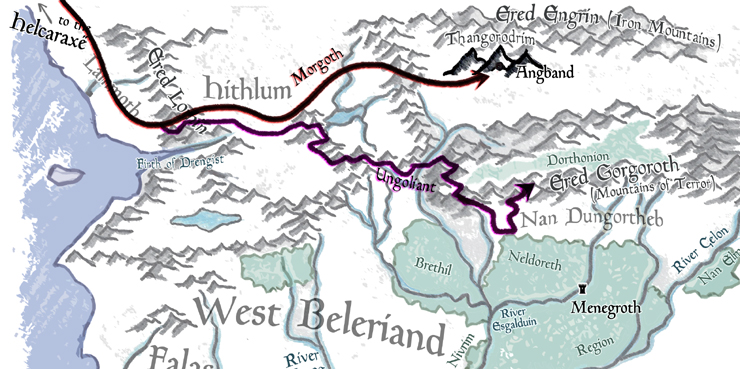

So basically two great hosts of Orcs come around Thingol’s woodland realm on either side, launching raids from two big camps. In Western Beleriand, these hordes cut off Thingol’s contact with Círdan.

But in Eastern Beleriand, he is able to light the beacons call for the aid of Denethor. Denethor and his Green-elves answer the call, and so two Elven armies clamp down on that eastern front—Thingol’s own army coming out of the forest of Region and the woods of Ossiriand. And this is the first of oh-so-many battles in what will be collectively known in the history books as the Wars of Beleriand. And in this first battle, the Orcs are defeated.

…and those that fled north from the great slaughter were waylaid by the axes of the Naugrim that issued from Mount Dolmed: few indeed returned to Angband.

Man, I love that wording. Interestingly, there’s no talk of Thingol even asking for the Dwarves’ aid. They just come out from their mountain city as a matter of course: “Orcs are coming; Da, get the axes,” seems to be their sentiment. I mean, they helped the Elves make their weapons. They know what it’s all about, and they’ve probably clashed with Orcs before.

But this famous first battle was a Pyrrhic victory; the Green-elves of Ossiriand weren’t heavily armed—they didn’t have the weapons of their Sindar friends—but the Orcs sure were, being “shod with iron and iron-shielded and bore great spears with broad blades.” Denethor himself is slain along with “all his nearest kin about him” (a motif we’ll sadly see again and again in Middle-earth).

Thingol is pissed. He and his forces come and slay Orcs “in heaps.” So aggrieved are the Laiquendi by the loss of Denethor that they take no new king. They mostly hide themselves away from this point on, though we’re told some of them do migrate over to join with Thingol’s melting pot of mostly-Sindar.

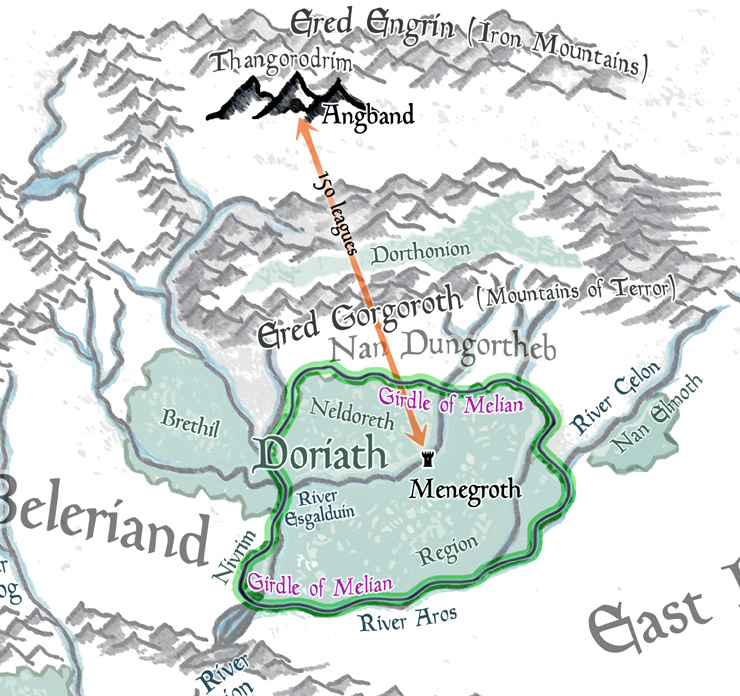

In the west the Orcs are not defeated, and they drive Círdan and his people right to the water’s edge, presumably killing many before eventually pulling back to Angband. Thingol and Melian realize just how dangerous things are going to get now that Morgoth is enthroned in Angband—which we’re told is one hundred and fifty leagues from the bridge of Menegroth. That’s roughly the distance between New York City and Cleveland, Ohio. Or as Tolkien puts it: “far and yet all too near.”

The King and Queen of the Sindar step up. Thingol calls out to all his people and bids them come closer—and many do come to pack themselves a little more densely into the forests of Neldoreth and Region. Melian then uses her Ilúvatar-gifted power and basically casts an epic spell—she sets a great invisible fence “of shadow and bewilderment” around these woods. Called the Girdle of Melian, it keeps out all creatures that she doesn’t expressly allow in. Those who try to enter find themselves confused and lost and wandering back out again. So basically if you want in, you have to be higher level than Melian or at least walk with a power that is. At this point, Thingol’s guarded realm is called Doriath.

Morgoth has only just tested his strength with this first assault on the much-hated Children of Ilúvatar, but it’s a sign of things to come. Beleriand is not safe. Morgoth’s monsters have the run of the place. Now there are only two sanctuaries: (1) Doriath with its Girdle-based security system and (2) the havens in the Falas region over by the sea, where Círdan dwells. If you’re not in one of these places, you’re on your own. Morgoth’s own personal power may have diminished over the ages, but that’s only because he’s placed so much of himself into his works.

So: that’s the state of things when Fëanor touches down on the shores of Middle-earth and burns the swan ships of the Teleri. He’s come to rule as king, he’s come for Morgoth, and he’s come for his Silmarils. “Ah, so this is the much-ballyhooed Middle-earth,” he might be thinking. “Nothing much going on over here! Easy enough to take charge.”

In the next installment of The Silmarillion Primer, we’ll find out what celestial bodies the Valar have been cooking up, and learn what region of Arda will alter its level of accessibility by taking a look at the eleventh chapter, entitled “Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor.”

Top image: “Angband” by Sergey Musin

Jeff LaSala can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. Tolkien nerdom aside, he wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books.